By Syed Ali Shah

29 Nov, 2025 08:37:23

Scholars: The Guardians of the Faith

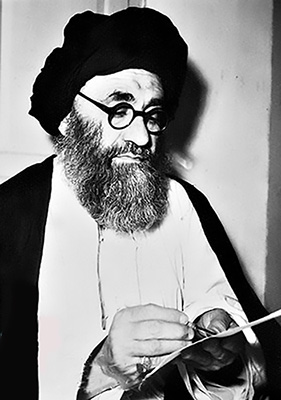

The Marja, Who Never Made the Pilgrimage

بِسْمِ اللهِ الرَّحْمَنِ الرَّحِيمِ

The Marja, Who Never Made the Pilgrimage

Every year, countless pilgrims travel to the sacred lands to perform the holy rites of Hajj. Yet, even among the most devoted, there are souls who, despite their faith and devotion, never make this journey. In Qom, when you decide to visit the Shrine of Lady Fatima Masuma (a), you can take several routes. One of the paths runs through Eram Street. Many travelers pass it without noticing its small but meaningful corners. Among them is the grave of Ayatullah Sayyid Shahab al‑Din Mar’ashi Najafi قدسسره.

Besides it lies one of Iran’s oldest libraries, filled with centuries of knowledge and care. Only here, at this quiet turn before the shrine, does the presence of a remarkable scholar appear. He was a man devoted to faith, to teaching, and to serving Islam through action, not just words. Like many other visitors, I had the privilege to be at his grave several times, and even inside the secure library that holds many ancient Islamic Manuscripts. At this site, the Maghrebeen congregational prayer normally takes place on the ground level of the building. Today, his legacy lives on, preserved with devotion by his son, Sayyid Mahmoud Mar’ashi Najafi, continuing to inspire those who seek knowledge and spirituality.

I Was Never Able , مستطیع:

Ayatullah Sayyid Shahab al-Din Mar’ashi Najafi قدس سره, son of Ayatullah Sayyid Shams al-Din Mahmoud Husayni Mar’ashi, was a great jurist, a scholar of literature, and a noble transmitter of hadith in the world of Islam and Shi‘ism. He studied under the guidance of the teachers of Najaf, receiving profound spiritual training. In time, he became a teacher himself, dedicating nearly his entire life to guiding students and serving Islam. Yet, until his final moments, he never traveled for the pilgrimage.

His son, Sayyid Mahmoud Mar’ashi, recounts: “Until the day my father passed away, he never reached the House of God. Even in his last days, people would ask him, "How have you still not made the pilgrimage?" He would answer, "I was never able" مستطیع. In Islam, if a person is not able (مستطیع in Arabic), Hajj is not obligatory for them.”

Once, a man said to him, “Agha, you have access to so much money—khums and donations. How can you not be able to go?”

He replied, “This money is not mine. It belongs to religious dues: the Imam’s share, the share of the Sayyids, and the rights of the needy. I cannot use it for myself and go to Mecca while I own nothing of my own. So I am not able.”

Another person suggested, “Perhaps someone may host you one day.” He responded, “I must know the source of the money used to host me. It must not contain doubt. My heart wishes that anything I spend on myself will truly be my own.”

His Life Devoted to Books:

He devoted his entire life to safeguarding the written treasures of the Islamic world, seeing in every manuscript a fragment of the Ummah’s intellectual soul. His mission began in Najaf, where he witnessed a painful and alarming reality: a man, acting as a broker for the foreign occupying forces, routinely bought rare books at auctions of deceased scholars’ libraries and secretly smuggled them to foreign countries, confirmed by britishmuseum.org. Realizing that the heritage of Islam was being drained from its birthplace, Ayatullah Marʿashī قدس سره vowed to resist this plunder. He worked nights in a rice mill, reduced his meals, and accepted prayers and fasts on behalf of others to earn money, all to rescue manuscripts before they fell into foreign hands. Over the years, he amassed a vast collection of rare and precious works, each saved through sacrifice and personal hardship. When he later migrated to Iran, he brought with him all the manuscripts he had preserved in Najaf, eventually establishing in Qom one of the greatest libraries of Islamic manuscripts, ensuring that these treasures remained in the heart of the Muslim world, accessible to scholars and protected for generations to come

A Life of Simplicity:

If anyone gave him religious dues at the shrine, he insisted that the money be spent the same night. He never allowed it to remain until morning.

Once, someone handed him such money. When he returned home, he said, “Call the baker and give him this. I must free myself of this responsibility. God may take my life tonight, and this money must not remain on my conscience.”

In His Final Days:

On his final visit to the shrine of Lady Fatima Masuma (a), he performed ghusl and ablution. After the evening prayers, he returned home, his only possession a mere eight to ten tomans in bills. He had no money in any bank or kept with anyone, except for small sums entrusted to a few devout merchants in Tehran, Qom, and other cities. He had made them swear that even his children should not know about it. Only after his death did we learn of this, according to his son. Through these men, he would send money to poor families, who delivered it using only addresses, unaware of the donors’ identity.

Daily Life and Attire:

He usually ate one simple meal a day. In summer, it was bread with yogurt or buttermilk; in winter, a humble stew. About his clothing, “Since I first knew myself, I have never worn foreign cloth.” Everything he wore was made in Iran. Once, a tailor mentioned that even if the buttons come from abroad. He refused to wear them and requested, “Make buttons from Iranian braid, so even the buttons are not foreign.”

Throughout his life, he never used religious dues for food or clothing. These came from personal offerings of those who loved him, saying, “Agha, this is our vow (نذورات) for you. Use it as you wish.” He never touched the public treasury for his own needs and was extremely cautious with such funds. He often warned, “These dues burn like fire. Be careful. Do not let your lives become stained by them.”

Students who brought dues for him to receive or return were often advised: “I give you only what is necessary for your livelihood. Spend it with great care. You are scholars. You must guard the public trust more than anyone. If a scholar is careless with this, what can we expect from others?”

الإمامُ عليٌّ عليه السلام : مَن نَصَبَ نَفسَهُ للنّاسِ إماما فليَبدأ بتَعليمِ نَفسِهِ قَبلَ تَعليمِ غَيرِهِ ، و ليَكُن تأديبُهُ بسِيرَتِهِ قَبلَ تأديبِهِ بلِسانِهِ ، و مُعَلِّمُ نَفسِهِ و مُؤدِّبُها أحَقُّ بالإجلالِ من مُعَلِّمِ النّاسِ و مُؤدِّبِهِم .

Amir al-mu'minin Imam Ali (a), said: Whoever places himself as a leader of the people should commence with educating his own self before educating others; and his teaching should be by his own conduct before teaching by the tongue. The person who teaches and instructs his own self is more entitled to esteem then he who teaches and instructs others.

He was a living example of the words of his ancestor, Amir al-Mu’minin Imam Ali (a)

Date Published: 9 Mordad 1397 (July 31, 2018)

Source:

Special Issue of Shihab-e-Shari‘at

https://www.britishmuseum.org/about-us/british-museum-story/collecting-histories

Nahjul Balagha Short Saying#73

Author: Syed Muhamad Ali Jaffery

Tags:

Share:

Leave a Reply

Recent Posts

11 Feb, 2026

Justice Vs Expediency

16 Dec, 2025

Social Pressures and Islamic Principles

30 Nov, 2025

Allah SWT The Creator

Need Help? We Are Here To Help You

Contact Us

Subscribe Newsletter

Stay Updated with